Things began to unravel in the summer of 2015. By that Christmas, Sgt. 1st Class Johnnie Johnson would be gone, never to be heard from again.

Sometime in spring 2015, Johnson told a friend that he’d listed her as a reference for a background check related to his secret security clearance. But he was stressed. When she asked him why, he hesitated. Later, he said that if the investigators asked whether he was married, she should say yes.

A tug on that thread wound up pulling his life apart, exposing several more lies. In late 2015, as investigators closed in, Johnson slipped away. He took nothing but a debit card and his handgun.

In the four years the woman had known Johnson, he never told her about his marriage, she said in a sworn statement to the Army Criminal Investigation Division in June 2015. The statement was part of the redacted CID record of the investigation provided to me under the Freedom of Information Act.

The soldier’s secret gets out

When the background investigators didn’t end up asking the woman about Johnson’s marital status, she confided in a family member about the request. That relative, who was also an investigator in the military, advised her to report the matter to authorities.

So she did.

Johnson would eventually tell her that he’d been married “some years earlier,” but things didn’t work out and they parted ways after his wife divorced him.

Except—and this is the rub—the Army didn’t know about the divorce. He never turned in the divorce decree, so he continued to receive a housing allowance and other pay and benefits of a married soldier for over a decade.

She told the CID investigators that her relationship with Johnson was casual, on-again-off-again, and not romantic. After talking to investigators, she agreed to contact Johnson for them. She told him CID was inquiring about his marital status.

“That’s not possible,” he said via text to her.

She told him to call CID if he didn’t believe her.

“Like, are you saying that to mess with me?” he said. “Why would you do that? Please don’t do that to me I really can’t take that.”

The soldier confesses to housing allowance fraud

A sergeant first class with 17 years in the Army, including five combat tours in the Middle East, Johnson was serving with a U.S. Army Central Command unit on Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina.

In early July 2015, he met with criminal investigators from nearby Fort Jackson.

But the investigators had already spoken to Johnson’s ex-wife days earlier. She’d told them that she divorced Johnson 13 years earlier. And the day before they met with Johnson, the investigators got confirmation from a county clerk in Texas that the divorce decree had been filed. Johnson had signed it.

Johnson’s ex said they’d gotten married in December 1999 in Colorado Springs, Colo., a few months after meeting. They were stationed at Fort Carson. But shortly after they wed, things started to go south. He’d stay out all night, go to the clubs, she said.

Shortly after he got orders to Korea in 2000, she transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, where she met a noncomissioned officer who’d recently returned from Johnson’s unit in Korea. He told her that her husband was in trouble over there, barred from reenlisting or leaving the country until everything was cleared.

That’s when she began looking into the ending the marriage.

When the divorce was granted in 2002, she took the decree to her unit and gave it to the VA as she was outprocessing from the Army, she told investigators.

A few years later, when Johnson was visiting Florida, he told her to get a dependent ID card at MacDill Air Force Base, telling her they were still legally married. She told him they weren’t and that she had a divorce decree. Still, she did get the ID card, though she said she never used it and had access to base because of her job at the time.

His ex said she never got financial support from him and didn’t know he was claiming her as a dependent, which he later confirmed to investigators.

In a recorded statement, Johnson said that he had falsely collected housing allowance and had knowingly submitted false paperwork to start, stop, or change the allowance, or for official travel benefits. CID estimated his actions cost the Army some $82,000 in improper pay and allowances.

After the interview, a CID investigator notified Johnson’s command that the soldier had had previous suicidal ideation and had driven his car into a pole.

The soldier’s other lies were soon exposed

CID began looking into the soldier’s pay and entitlements over the 13 years since his divorce to determine how much he had obtained under false pretenses.

But as criminal investigators dug in further, they found a few more surprises.

Johnson’s record in the interactive Personnel Electronic Records Management System, or iPERMS, showed that the soldier had graduated from the Army’s Pathfinder and Air Assault courses. His official photo shows him wearing the badges for both. And his iPERMS records showed that he had both a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree from the University of Florida.

All of that was falsified, investigators found.

In fact, when Johnson had met with the investigators, he’d told them his highest level of education was high school graduate.

It turned out Johnson had been dropped from a Pathfinder course that a mobile training team, or MTT, provided at Fort Eustis, Virginia, in 2012. But in iPERMS it said he’d graduated the course in 2009, on a document that one expert told the investigators looked liked a forged certificate she’d seen before.

There was no record on his official Army training transcripts to show he had completed the Air Assault or Pathfinder courses. And, while the University of Florida registrar’s office could not say conclusively, it looked like he’d never gone to school their, either.

Six months after CID first questioned Johnson about his marital status, investigators met with him on December 7, 2015, and advised him of his rights again. He requested an attorney and declined to take a polygraph test. He did consent to letting investigators collect his degree certificates and transcripts, which turned out to have some aberrations when investigators inspected them.

Less than a month later, the University of Florida confirmed to investigators that the documents were false and that Johnson had never attended the school.

But by then Johnson had already been declared absent without leave weeks earlier. He would be declared a deserter days later.

The soldier goes missing after meeting with CID

Johnson was supposed be at a 0630 formation the morning after his last meeting the CID, December 8, 2015. But he never showed.

Several members of the unit tried to call him throughout the day.

He didn’t answer.

So a captain called the local sheriff’s department, and that evening a couple noncomissioned officers went over to Johnson’s house to check on him.

When sheriff’s deputies arrived, they found the house unlocked. They entered, but Johnson was nowhere to be found. His debit card and handgun were also missing.

Everything else seemed to be in place, including his vehicles—a 2012 Harley-Davidson edition Ford F-150 and a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Johnson’s command asked CID to look into next of kin and other vehicles Johnson might’ve owned.

Meanwhile, the local county sheriff’s department searched Johnson’s home and the surrounding area to no avail. The department initiated a missing person’s case.

Was the missing soldier involved in a bank robbery?

A few days later, on December 11, 2015, two men robbed a bank in Duncan, S.C., about two hours northwest of Columbia, where the missing 36-year-old soldier had been living. CID requested photos of the robbery suspects, seemingly wondering if one might be their missing man.

The photos showed “what appeared to be two black males wearing hooded sweatshirts and bandanas” entering Palmetto Bank. But the photo quality was too poor to tell if either of their weapons was the same type as Johnson’s 9mm handgun, investigators said.

CID also contacted Navy Federal Credit Union around this time and found that Johnson had last used his debit card on December 7, 2015, at a convenience store in Edgefield, S.C. Security camera footage showed that Johnson had bought case and a pack of Newport cigarettes.

That was the last he was seen.

Friends said they hadn’t spoken to him since that night, though one first sergeant did tell investigators he had a missed call from Johnson early on the morning of December 8.

Sometime shortly after his disappearance, some of his friends moved his vehicles and left him a note telling him to contact them to get the property when he returned.

CID issues a BOLO for the missing soldier

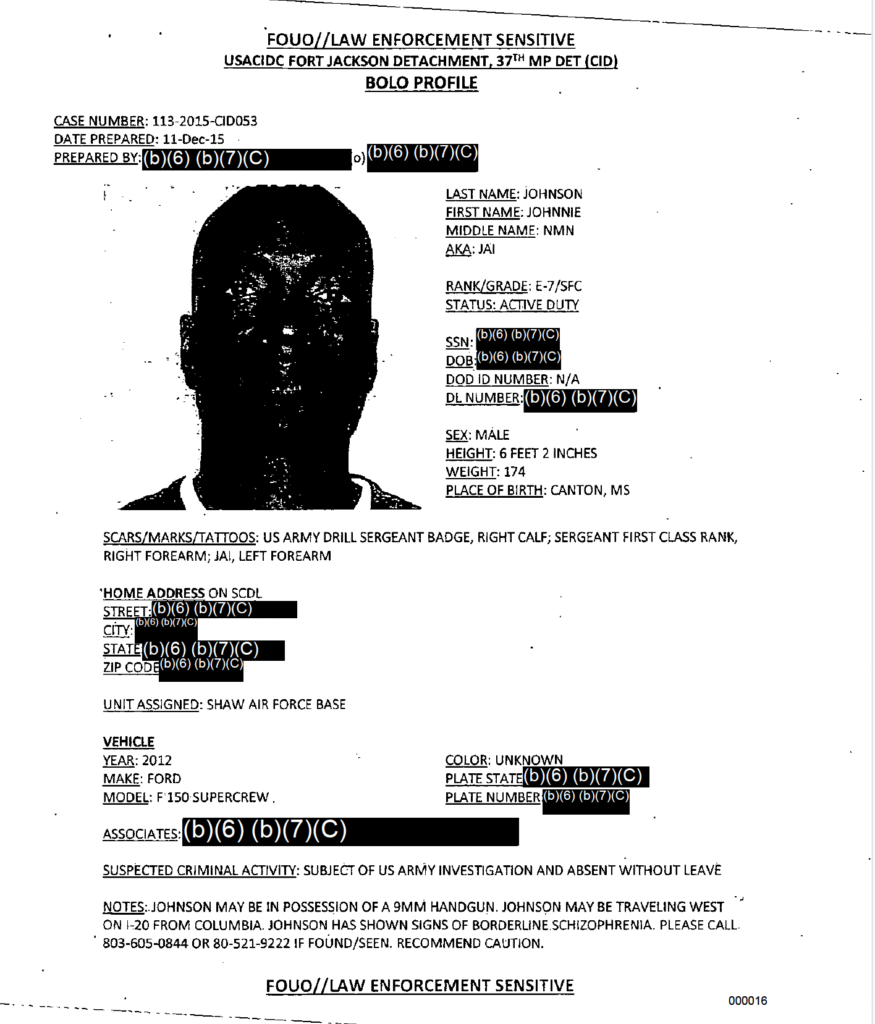

CID issued a “be on the lookout” profile for Johnson on the day of the bank robbery, stating that he might be armed and “has shown signs of borderline schizophrenia.”

This last part about his mental health appears to come from the sheriff’s office report, which is not included in the CID records, but which the case file summarize as saying Johnson was taking medication to treat borderline schizophrenia. A later CID review of Johnson’s military medical files found no behavioral health or mental illness treatment or prescriptions.

In January 2016, CID questioned one of Johnson’s friends, who said they’d had an argument in late November 2015, after Johnson sent her a text message with a love song in it, but then didn’t respond to her text. She went over to see him and he was drunk and angry, telling her she would never have to see him again.

The woman, whose name is redacted in the record, also told investigators that Johnson frequented websites fling.com and onlinebootycall.com. Who she said he would have sex with was redacted, however. She said he maintained several email addresses and seemed to live a “double life.”

The manhunt for the missing soldier spans months

CID continued to chase down leads on Johnson’s possible whereabouts into 2017, interviewing friends and family, checking his bank activity, running down potential storage units he may have used, and so on.

The investigators snooped on the Facebook page of the motorcycle club Johnson had belonged to, the South Cak Ryderz, trying to determine the date of a party the club posted photos of, featuring Johnson, after the soldier’s disappearance.

Johnson had little contact with family members in the 10 years prior to his disappearance, one person told them. He’d made plans to visit a family member for Thanksgiving 2015, but cancelled on the day.

A former girlfriend, a fellow soldier who gave him the handgun as a birthday present, told CID that they remained friends after the breakup, but they fought about how he spent money on things he couldn’t afford or didn’t need.

He had borrowed about $3,000 from her, but when she asked to be paid back, he got “mean and hateful,” she told investigators. He paid her $1,500 after she threatened to tell his command, and they never spoke again.

“On 23 Dec 2015, I sent him a message on his Facebook account wishing him a Merry Christmas but he didn’t respond,” she said in a statement to CID.

The case goes cold before a body is found

The local sheriff’s office turned its case on Johnson over to its cold case unit in 2018. The sheriff’s department suspected he’d died by suicide, but had found no evidence to confirm it, Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott said in a December 2020 press conference.

Then, three years after the soldier’s disappearance, a person walking in an area less than a mile from Johnson’s home found a human jaw bone. DNA testing would later determine the bone was Johnson’s.

In October 2020, the local sheriff’s department searched the area with cadaver dogs, locating more remains and a Harley Davidson jacket. Later that month, authorities found a gun.

Lott announced in the December 2020 press conference that the remains were Johnson’s.

Johnson’s death was ruled a suicide, Lott said. The CID records show Johnson appears to have shot himself in the head. Wild animals picked over his remains.

Johnson, of Canton, Miss., joined the Army in June 1998 as a petroleum supply specialist, U.S. Army Central said in a press release after his remains were identified.

His awards and decorations include the Bronze Star Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, Army Commendation Medal, and others.

CID’s investigation confirmed the validity of those medals.

The official Army CID records released under FOIA

Here’s the Army CID case file on Johnson. For uploading purposes, it’s divided into two files.

Army-CID-Johnnie-Johnson-INV-FA24-1351-GARLAND-CHAD-Release-Packet Army-CID-Johnnie-Johnson-INV-FA24-1351-GARLAND-CHAD-Release-Packet-2-1Keep Reading

Sign up

You may eventually get a newsletter.

The Chad Garland Writes For You newsletter doesn’t exist yet, but one day it will. Possibly.

The free weekly newsletter will take no time to read, because it’ll probably just pile up in your inbox.